Precision Spectroscopy of Few-Electron Systems and Fundamental Physical Tests

Atomic and molecular spectroscopy provides a critical window into the internal structure of matter and its interactions. Through precision spectroscopic studies of atoms and molecules, we can test fundamental physical laws with extremely high accuracy, determine fundamental physical constants, and extract key parameters of atomic and molecular structures. Our research group has long been dedicated to precision spectroscopic measurements of few-electron systems such as molecular hydrogen and helium atoms. We have achieved world-leading accuracy in measuring transition frequencies in two-electron systems, including helium atoms and hydrogen molecules. These results not only provide stringent experimental tests for quantum electrodynamics (QED) theory but also contribute to the precise determination of fundamental constants and further probing of the Standard Model. Welcome to learn more about our cutting-edge explorations!

Precision Spectroscopy of Hydrogen Molecules

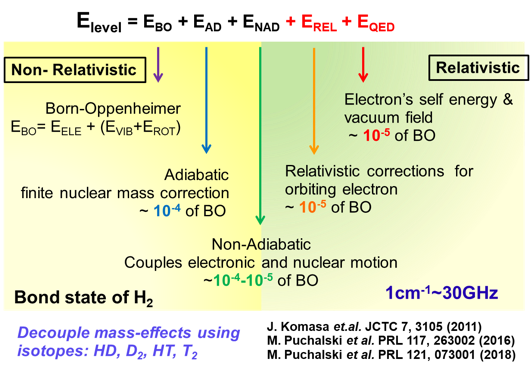

Hydrogen molecules (including H2, HD, D2, etc.) are the simplest neutral molecular systems in nature, consisting of two nuclei and two electrons. They represent one of the few many-body systems that can be solved accurately from first principles of quantum mechanics, and have long been at the forefront of modern physics research.

In the early days of quantum mechanics, Heitler and London explained the experimental measurement and theoretical calculation of the dissociation energy of H₂, revealing for the first time that "chemical bonding" is essentially a quantum phenomenon. Over the following century, the hydrogen molecule has been established as an ideal system for testing relativistic effects and quantum electrodynamics (QED). Recent theoretical studies show that high-precision quantum calculations of hydrogen molecular energy levels strongly depend on high-order relativistic and QED corrections, and are highly sensitive to fundamental constants such as the proton charge radius and the proton-to-electron mass ratio. Therefore, precision spectroscopic measurements of hydrogen molecules not only provide high-precision tests of QED theory but also enable accurate determination of fundamental constants in molecular systems.

Using ultra-sensitive cavity ring-down spectroscopy, we achieved precision measurements of the near-infrared electric quadrupole transitions in H2 molecules with uncertainties at the then state-of-the-art level, verifying quantum theoretical calculations with up to 9 significant digits. Furthermore, by combining optical frequency comb-calibrated cavity-enhanced saturation absorption spectroscopy, we observed for the first time the Doppler-free Lamb-dip spectrum of overtone transitions in HD molecules, with frequency measurement accuracy reaching 10 significant digits. This demonstrates the potential of the method for determining fundamental constants such as the proton-to-electron mass ratio.

In collaboration with scientists from the Netherlands and Switzerland, we successfully developed a "chirp"-free vacuum ultraviolet laser system, improving the measurement accuracy of the H2 dissociation energy to the sub-MHz level. Further enhancement of this accuracy is expected to provide key experimental evidence for determining the proton charge radius.

Looking ahead, we plan to advance the measurement accuracy of hydrogen infrared spectroscopy beyond 10-10 by developing new cavity-enhanced spectroscopic detection technologies, combined with high-precision mid-infrared laser sources, cryogenic environments, and molecular beam techniques. Based on this, we aim to achieve high-precision determination of a series of fundamental constants such as the proton-to-electron mass ratio and further explore "new physics" beyond the Standard Model.

Precision Spectroscopy of Helium Atoms

Helium is the simplest multi-electron atom, with both experimental and theoretical accuracies exceeding 10-11, making it an ideal system for validating quantum electrodynamic calculations and testing fundamental physical constants.

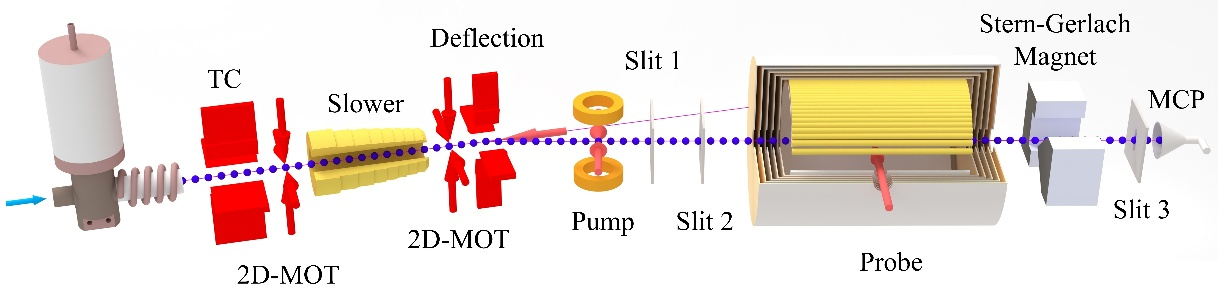

Fig. 1 Helium atomic beam setup

We have constructed a metastable helium atomic beam apparatus at the University of Science and Technology of China. This setup integrates laser cooling techniques to cool, compress, and deflect metastable helium atoms generated by RF discharge, enhancing beam intensity. Single quantum state detection is achieved through optical pumping and gradient magnetic fields.

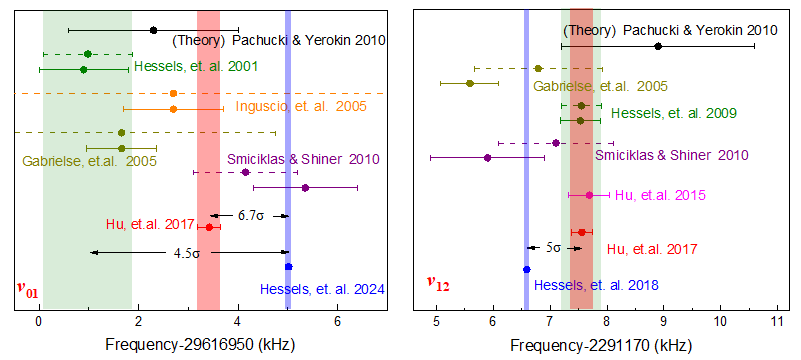

Fig. 2 Comparison of helium-4 23P fine structure results

Current helium beam spectroscopy focuses on fine structure and absolute frequency measurements. Our group has determined the fine structure splittings of helium-4 atoms for 23P0-23P2 and 23P1-23P2 as 31,908,130.98±0.13 kHz and 2,291,177.56±0.19 kHz, respectively, ranking among the most precise measurements reported internationally to date (as shown in Fig. 5). However, discrepancies remain in fine structure results: the Hessels group at York University (Canada) obtained ultra-high precision using an improved microwave method, but their results deviate significantly from QED predictions and other experimental values. Future improvements, such as ionization detection, will eliminate quantum interference effects and are expected to enhance the determination of the fine-structure constant α in atomic systems to a precision of 2×10-9.

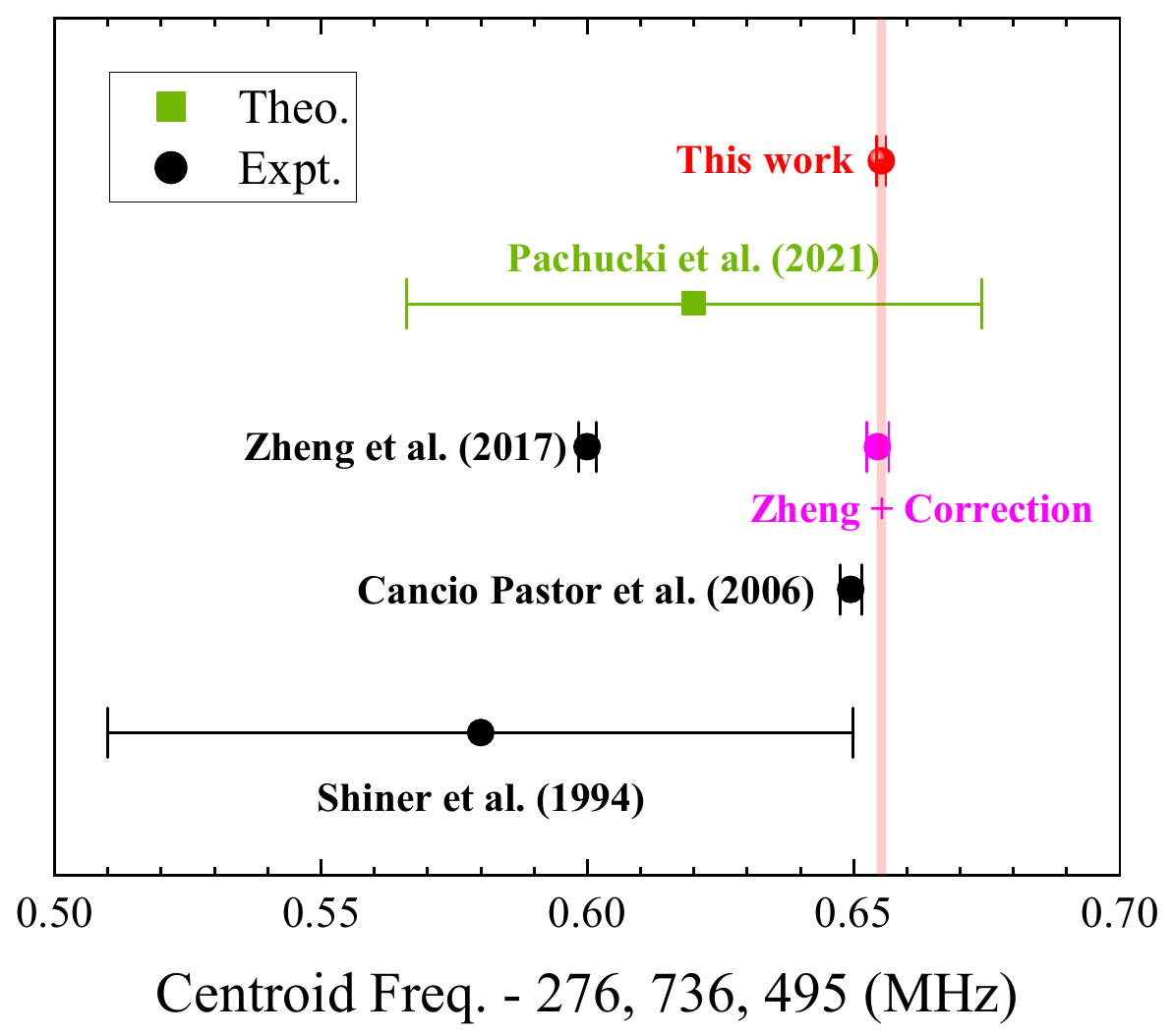

Fig. 3 Comparison of 23S-23P transition center frequency results

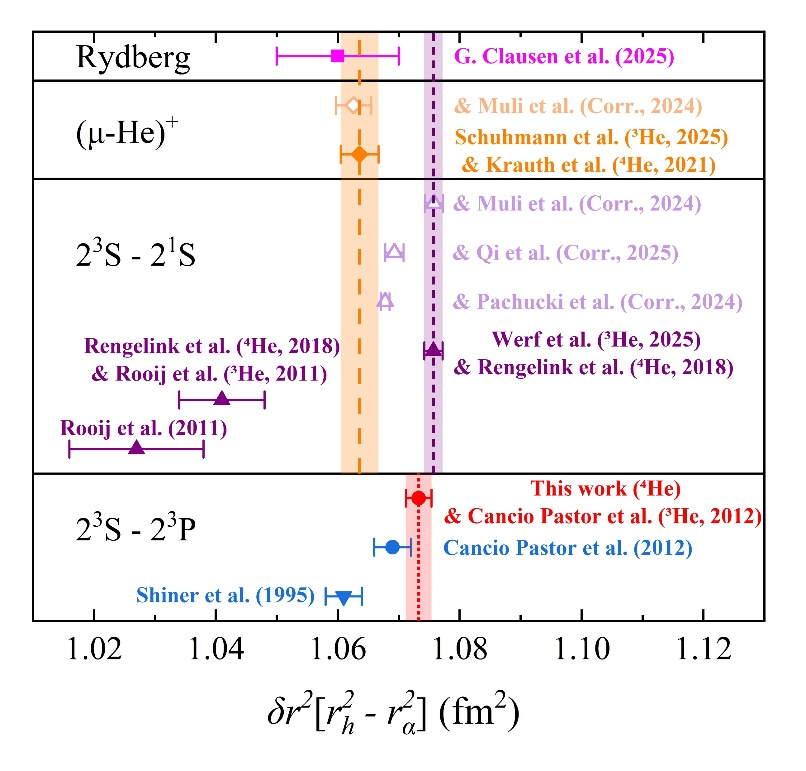

Fig. 4 Summary of helium atom isotope shift results

In absolute frequency measurements of the 23S-23P transition, using a traveling-wave detection scheme and velocity-varying measurements, we identified a systematic error due to post-selection effects, which can cause deviations exceeding 50 times the measurement precision. We have determined the absolute frequency of this transition in helium-4 atoms with sub-kHz accuracy, achieving the highest international precision. Future work will involve high-precision measurements of the same transition in helium-3 atoms to obtain independent isotope shift data. By comparing these results with other helium transitions and muonic helium ion measurements, we aim to determine the helium charge radius and contribute to resolving the "proton radius puzzle."