Manipulation and precise measurement of molecular quantum states

A fundamental task in the study of chemical reactions is to understand how to use the reaction transition states to control the rate of chemical reactions and product distribution. Therefore, the direct observation of reaction transition states has long been regarded as a "holy grail" in the field of chemical science research. However, for most chemical reactions, the lifetime of the reaction transition state is extremely short (on the femtosecond scale; 1 femtosecond is equal to 10-15 seconds), making the direct observation of these short-lived chemical reaction transition states extremely difficult. A reaction resonance state is a quasi-bound state with a certain lifetime formed by a chemical reaction system in the transition state region, analogous to the vibrational-rotational states corresponding to characteristic spectral lines in molecules. It provides an opportunity for the direct observation of the behavior of chemical reactions near the transition state, thereby enabling in-depth studies on the details of chemical reactions using resonance states. At a deeper level, studying reaction resonance states can also help us understand how quantum mechanics directly influences the dynamic processes of chemical reactions, which holds significant academic importance for our fundamental understanding of chemical reaction processes.

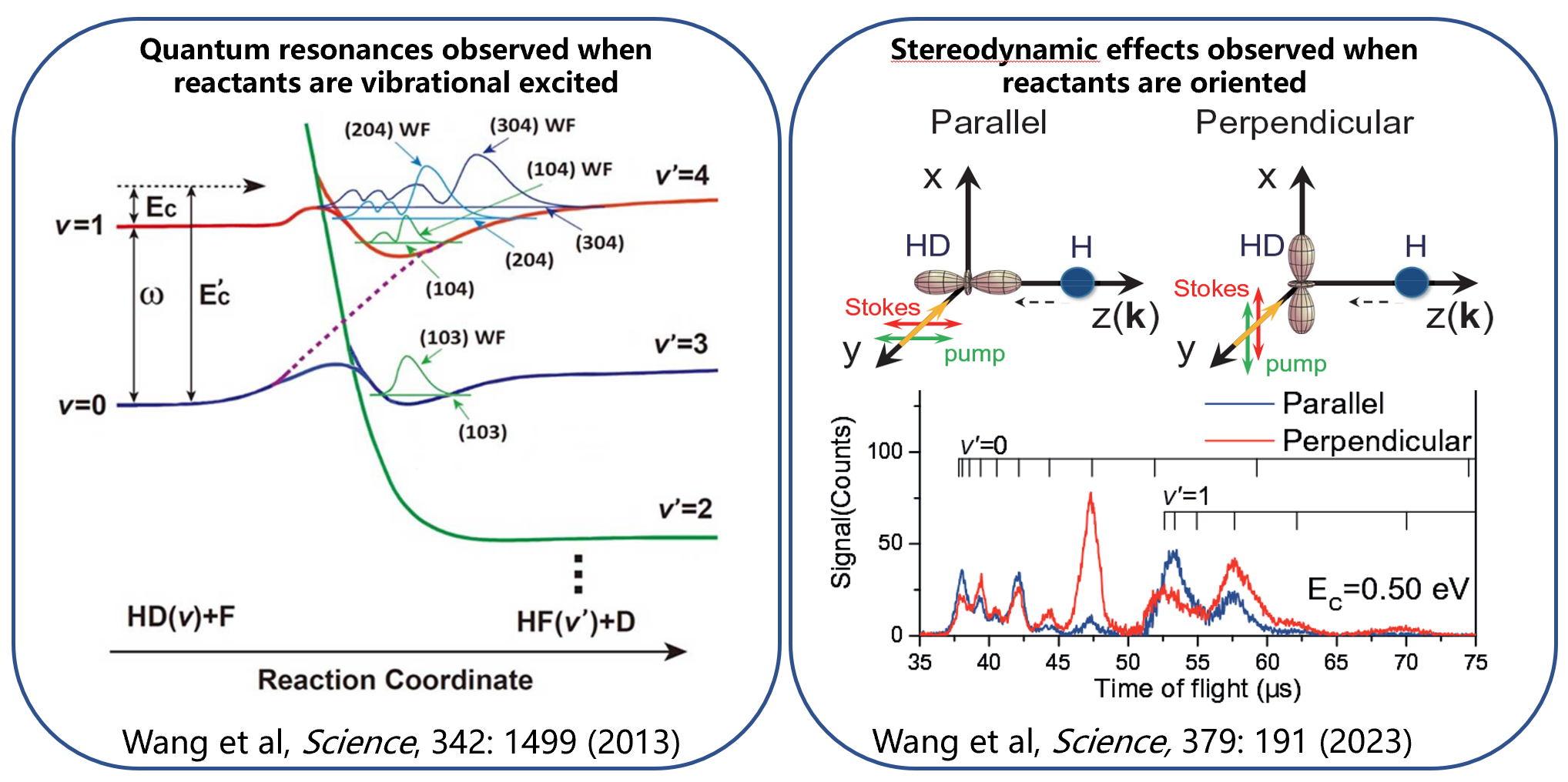

With the in-depth study of chemical reaction mechanisms, it has been found that preparing molecules into vibrationally excited states allows the observation of more abundant quantum resonance phenomena (as shown in Figure 1). These resonance states can only be accessed through the vibrational excitation of reactants, rather than through an increase in translational energy. These studies indicate that, for chemical reactions, molecular vibrational excitation not only provides energy but also opens up new reaction channels, allowing us to observe resonance phenomena that cannot be detected in ground-state reactions. Latest research shows that by manipulating quantum states, it is possible to control the orientation of chemical bonds in reactants and achieve precise stereodynamic control of chemical reactions. Behind these findings lies a more general scientific question: do these quantum resonances and stereodynamic effects exist in more reaction systems? Uncovering and understanding these effects will help us gain a deeper insight into the microscopic nature of chemical reactions. Nevertheless, the technology for preparing single quantum states of molecules remains highly challenging. Currently, there are no effective methods for manipulating molecules and preparing their quantum states for molecules of chemical interest.

We propose that the preparation of molecular vibrational-rotational quantum states can be achieved using high-precision continuous-wave lasers. Traditional vibration quantum state preparation technologies based on pulsed lasers mostly utilize the principle of Raman spectroscopy (as shown in Figure 2). Pulsed lasers have high energy, thus offering high excitation efficiency; however, the duty cycle of pulsed light is very low, resulting in a low proportion of excited states in the entire molecular beam. Limited by the cross-section of Raman transitions, pulsed excitation technology is currently only applicable to the preparation and regulation of low vibrational excited states. When a continuous-wave laser interacts with a molecular beam, it can excite all molecules in the beam. This method has good universality and is applicable to most molecules. However, molecular vibrational transitions are relatively weak; for example, the infrared vibrational transitions of molecules are generally 6–8 orders of magnitude weaker than atomic transitions. To achieve high-efficiency preparation of vibration quantum states, kilowatt-level power is required. Moreover, continuous excitation demands precise control over the laser frequency and phase, which imposes higher requirements on light sources and laser control technologies. The high-precision laser and optical cavity enhancement technologies developed in the laboratory can not only precisely control the frequency and phase of the laser but also achieve an equivalent power gain of 4–5 orders of magnitude for the laser within the optical cavity, making the high-efficiency excitation of molecular vibrational states feasible.

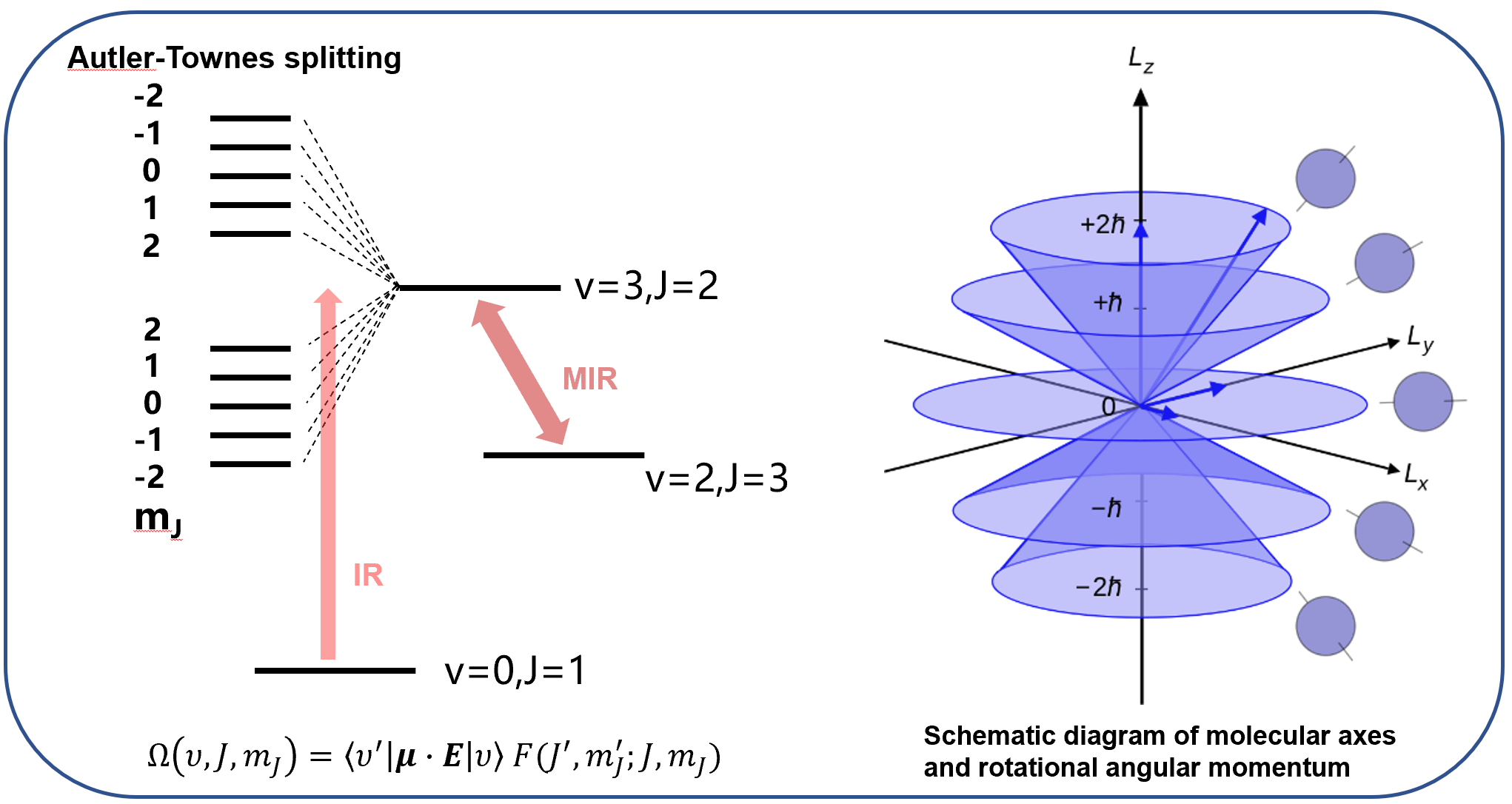

Based on the preparation of molecular vibration quantum states, we can also explore extensions in quantum optics. As shown in Figure 3, by allowing a mid-infrared (MIR) laser beam and a near-infrared (IR) laser beam to interact with molecules simultaneously, we can actively control molecular orientation and truly achieve the manipulation of molecular microscopic behavior. The principle is quite simple: using a high-intensity MIR laser to target specific molecular energy levels creates a strong interaction with the molecules. At this point, the vibrational quantum states of the molecules undergo a quantum optical effect known as Autler-Townes splitting. Both the rotational states (marked by the J quantum number) and even the rotational sublevels (marked by the MJ quantum number) of the molecules split into discrete energy levels with different energies. Another IR laser beam can then be used to prepare (polarize) the molecules into the selected sublevels. Since the MJ sublevel of a molecule represents the projection direction of the molecular rotational angular momentum onto the molecular axis, the selective preparation of molecules into specific sublevels means we can regulate the projection direction of the molecular angular momentum and control the microscopic spatial orientation of the molecules.

Currently, we have developed high-precision infrared light sources and advanced power enhancement technologies, achieving an equivalent power of several kilowatts and successfully realizing the preparation of molecular vibrational states. Building on these advancements, we have applied quantum optical technologies to the field of molecular quantum state regulation, enabling the manipulation of molecules at the microscopic level. Additionally, we plan to develop molecular cooling technologies to achieve macroscopic regulation of molecular motion. Equipped with these two powerful tools—microscopic and macroscopic regulation—we can conduct more refined studies on molecular dynamics and high-precision spectroscopy.